Greetings to Marshal of the Soviet Union Konev on his 75th birthday, 1972, from Colonel General Ivan Shkadov.

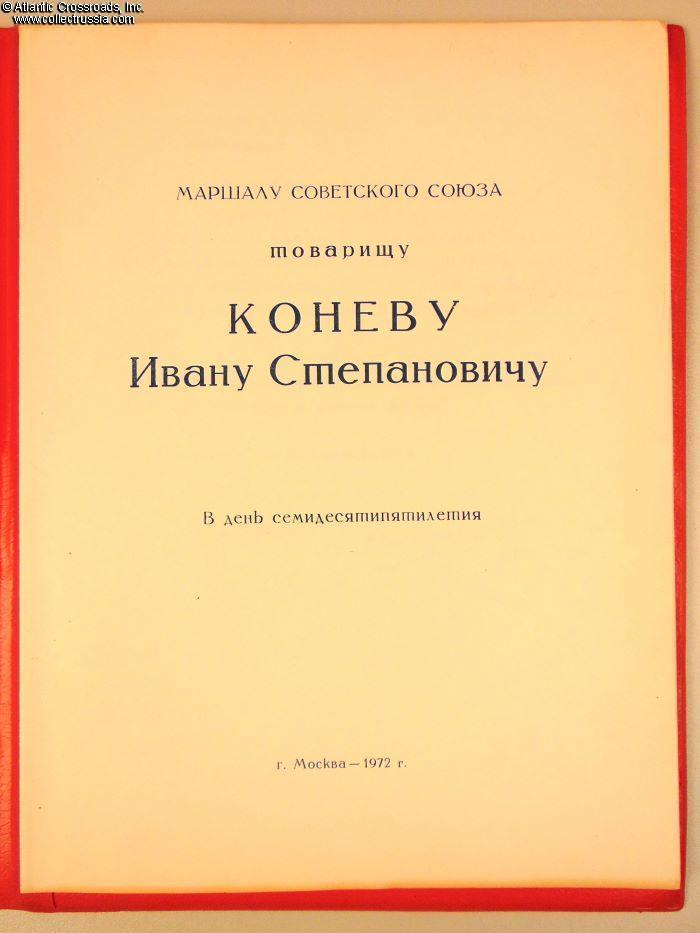

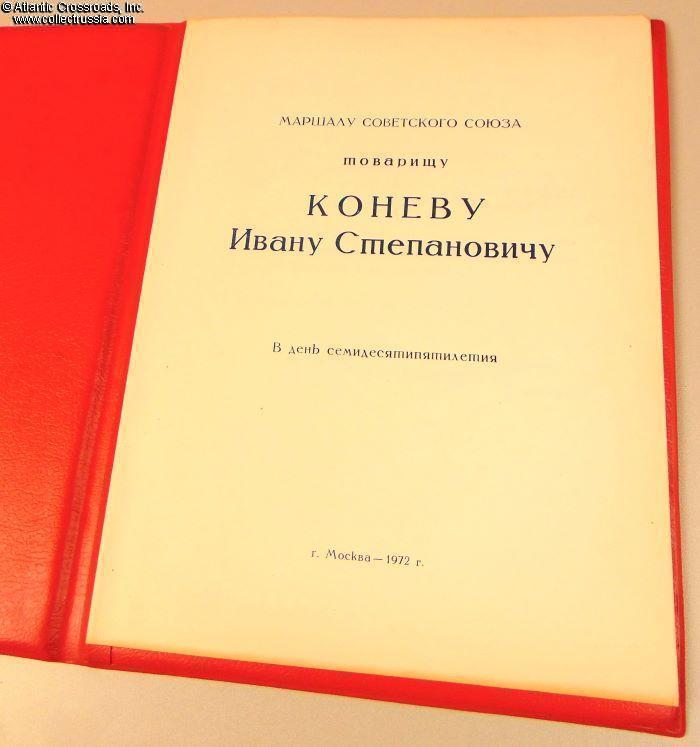

In large red plastic-wrapped presentation folder measuring 9 ½" x 12". The document is also a 2-page folder. The title page reads "To Marshal of the Soviet Union comrade Ivan Stepanovich Konev on the day of his 75th birthday. Moscow - 1972."

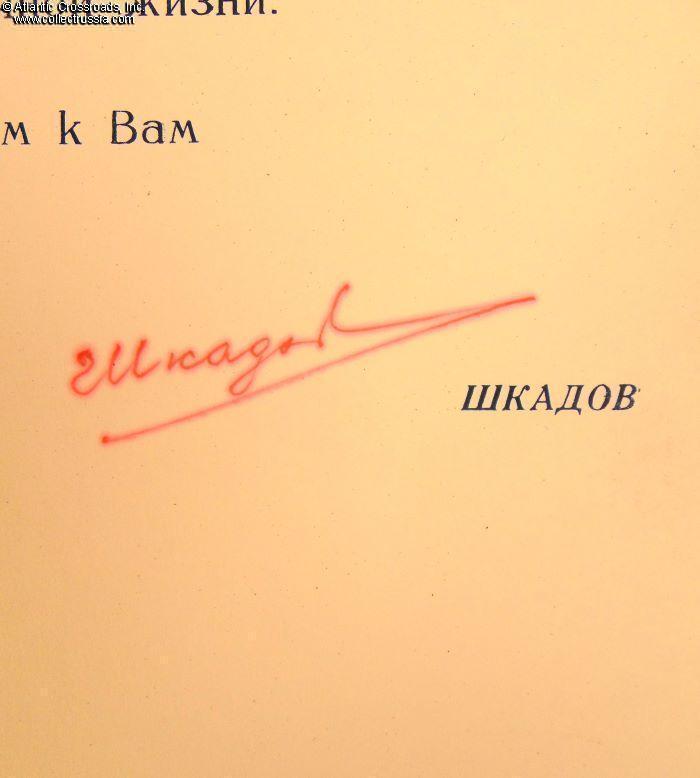

In excellent, superb condition. No wear to report except a tiny line of discoloration along the top and bottom edges, probably due to exposure to light. The red ink of Shkadov's hand signature has spread into the paper a little, creating an interesting 3D shade effect.

Col. Gen. Ivan Shkadov (Иван Ни&#

In large red plastic-wrapped presentation folder measuring 9 ½" x 12". The document is also a 2-page folder. The title page reads "To Marshal of the Soviet Union comrade Ivan Stepanovich Konev on the day of his 75th birthday. Moscow - 1972."

In excellent, superb condition. No wear to report except a tiny line of discoloration along the top and bottom edges, probably due to exposure to light. The red ink of Shkadov's hand signature has spread into the paper a little, creating an interesting 3D shade effect.

Col. Gen. Ivan Shkadov (Иван Николаевич Шкадов, 1913 - 1991), then Chief of the Personnel Department of the Ministry of Defense, future General of the Army (1975, Marshal rank equivalent), future Hero of the Soviet Union (1978). From 1964 to 1967 Shkadov was Chief of the group of military consultants in Cuba. Shkadov died in Moscow on 15 February 1991, run over by a car driven by a Cuban diplomat.

Ivan Konev (Иван Степанович Конев, 1897-1973), Marshal of the Soviet Union, twice Hero of the Soviet Union, was probably, next to Marshal Zhukov, the best known Soviet general during both World War Two and the Cold War. He and Zhukov were certainly the Soviet generals most frequently and correctly associated with the capture of Berlin. He was also known as the Soviet general whose troops marched into Czechoslovakia after Berlin's surrender and liberated the ancient city of Prague from the Germans.

Briefly a soldier in the imperial Russian army, he immediately enlisted in the Red Army, making it his career and rising steadily through its ranks (in spite of the fact that his father qualified in the Party's view as a "kulak" for having hired workers each year at harvest time). Perhaps it was because he took part as a young soldier in the crushing of the naval revolt in Kronstadt that his father's "sins" were not held against him. The fact remains that he moved steadily from one assignment to another and repeatedly took advantage of every advanced military course that he was encouraged to take.

By the late 1930s, he was one of the commanders of Soviet troops in Mongolia. By the time of German invasion in 1941, he quickly became a significant commander of the troops defending Moscow. While the defense was ultimately successful, there were innumerable disasters and it is generally believed that Stalin planned at one point to have him take the blame for everything that had gone wrong. Fortunately, Zhukov stood up for him and Stalin did not elect to carry through with a court martial. (Ironically, Konev did not reciprocate the favor when Zhukov found himself in the political crosshairs of the Kremlin decades later during the Cold War.) After the Germans were finally turned back from the gates of Moscow, Konev eventually wound up going from one success to another and after the crushing of German forces in the Korsun operation, he was promoted to the rank of Marshal of the Soviet Union.

While the Polish government may have torn down the Cracow statue that was erected in his honor after WW 2, the fact remains that it was his strategy of leaving a route open for the Germans to retreat through that enabled that city to be liberated by the Soviet army without also being turned into a pile of absolute rubble. While it is true that there were as many anecdotes about his ruthlessness as there were about any other WW 2 Soviet commander, it was definitely his determination to learn as much as possible about the enemy's disposition and intentions that enabled him to keep casualties amongst his troops on his fronts within reasonable limits. Very few commanders not only encouraged their subordinates to lead from the front but also then proceeded to do just that themselves despite any personal danger. Apparently, no one knew where he was liable to appear during the heat of battle.

Konev was a firm believer in the use of armor with air support, particularly when it was thoroughly coordinated. He also favored the overwhelming but somewhat selective use of artillery - abruptly stopping in mid-barrage just long enough to see where the Germans might still be capable of firing from and then, with new targets quickly identified, resuming fire that pounded everything into absolute dust, thereby saving the lives of many Soviet infantrymen during subsequent attacks.

The stories of the disagreements between Konev and Zhukov over the ultimate credit for the strategy and tactics of taking Berlin are too well known to go into here. The fact remains that after the Victory Parade in Red Square was over and Zhukov's white stallion was just another newsreel image, Konev's personal star clearly continued to rise in the Kremlin's estimation during the Cold War years while Zhukov's would eventually sputter - Zhukov never quite avoided the suspicions of "Bonapartism" leveled at him by Kremlin politicians who were in awe of his popularity.

In 1953, Konev was the Chairman of the Special Judicial Board of the Supreme Court of the USSR that tried and condemned secret police chief Beria. Later, as Warsaw Pact Commander in 1956, he was the man in charge of crushing the Hungarian revolt against the Soviets. His already tense relationship with Zhukov suffered a further blow the next year when an article appeared over his signature that proceeded to give chapter and verse about the latter's failures as a military commander and administrator.

Knowing Konev's no-nonsense reputation in the West for brutal forcefulness, the Kremlin appointed him Commander-in-Chief of Soviet Forces in Germany in 1961 just in time for the building of the Berlin Wall - even though he had technically retired the year before when he assumed the title of Chief Inspector of the Soviet Defense Ministry. It is obvious in retrospect that there was no way that Moscow was going to enter into a potential face-off with the American military over a crisis in occupied Berlin without having a Marshal in charge who projected the absolute image of Soviet power! Within two years, the German assignment had ended and Konev retired from active military leadership. He would eventually die of cancer in 1973.

Please note that the pen in our photo is for size reference.

$250.00 Add to cart